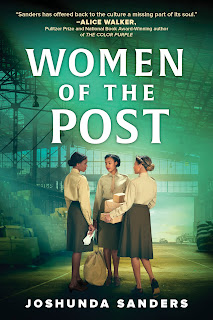

Women of the Post by Joshunda Sanders

About the Book:

For fans of A League

of Their Own, a debut historical novel that gives voice to the pioneering Black

women of the of the Six Triple Eight Battalion who made history by sorting over

one million pieces of mail overseas for the US Army.

Inspired by true events, Women of the Post brings to life

the heroines who proudly served in the all-Black battalion of the Women’s Army

Corps in WWII, finding purpose in their mission and lifelong friendship.

1944, New York City. Judy Washington is tired of having to

work at the Bronx Slave Market, cleaning white women’s houses for next to

nothing. She dreams of a bigger life, but with her husband fighting overseas,

it’s up to her and her mother to earn enough for food and rent. When she’s

recruited to join the Women’s Army Corps—offering a steady paycheck and the

chance to see the world—Judy jumps at the opportunity.

During training, Judy becomes fast friends with the other

women in her unit—Stacy, Bernadette and Mary Alyce—who all come from different

cities and circumstances. Under Second Officer Charity Adams's leadership, they

receive orders to sort over one million pieces of mail in England, becoming the

only unit of Black women to serve overseas during WWII.

The women work diligently, knowing that they're reuniting

soldiers with their loved ones through their letters. However, their work

becomes personal when Mary Alyce discovers a backlogged letter addressed to

Judy. Told through the alternating perspectives of Judy, Charity and Mary

Alyce, Women of the Post is an unforgettable story of perseverance, female

friendship and self-discovery.

Excerpt:

One

Judy

From Judy to The Crisis

Thursday, 14 April 1944

Dear Ms. Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke,

My name is Judy Washington, and I am one of the women you write about

in your work on the Bronx Slave Market over on Simpson Street. My husband,

Herbert, is serving in the war, so busy it has been months since I heard word

from him. It is the fight of his life—of our lives—to defend our country and

maybe it will show white people that we can also belong to and defend this place.

We built it too, after all. It is as much our country to defend as anyone

else’s.

All I thought was really missing from your articles was a fix for us,

us meaning Negro women. We are still in the shadow of the Great Depression now,

but the war has made it so that some girls have been picked up by unions, in

factories and such. Maybe you could ask the mayor or somebody to set us up with

different work. Something that pays and helps our boys/men overseas, but

doesn’t keep us sweating over pails of steaming laundry for thirty cents an

hour or less. Seems like everyone but the Negro woman has found a way to

contribute to the war and also put food on the table. It’s hard not to feel

left behind or overlooked.

Thank you for telling the truth about the lives we have to live now,

even if it is hard to see. Eventually, I pray, we will have a different story

to tell. My mother always says she brought us up here to lay our burdens down,

not to pick up new ones. But somehow, even if we don’t go to war, we still have

battles to fight just to live with a little dignity.

I’ve gone on too long now. Thank you for your service.

Respectfully,

Judy Washington

Since the men went to war, there

was never enough of anything for Judy and her mother, Margaret, which is how

they came to be free Negro women relegated to one of the dozens of so-called

slave markets for domestic workers in New York City. For about two years now,

her husband, Herbert, had been overseas. He was one half of a twin, her best

friend from high school, and her first and only love, if you could call it

that.

Judy had moved with her parents

from the overcrowded Harlem tenements to the South Bronx midway through her

sophomore year of high school. She was an only child. Her father, James, doted

on her in part because he and Margaret had tried and tried when they were back

home in the South for a baby, but Judy was the only one who made it, stayed alive.

He treasured her, called her a miracle. Margaret would cut her eyes at him,

complain that he was making her soft.

The warmth Judy felt at home was

in stark contrast to the way she felt at school, where she often sat alone

during lunch. When they were called upon in classes to work in groups of two or

three, she excused herself and asked for the wooden bathroom pass, so that she

often worked alone instead of facing the humiliation of not being chosen.

She had not grown up with friends

nor had Margaret, so it almost felt normal to live mostly inside herself this

way. There were girls from the block who looked at her with what she read as

pity. “Nice skirt,” one would say, almost reluctantly.

“Thanks,” she’d say, a little shy

to be noticed. “Mother made it.”

Small talk was more painful than

silence. How had the other Negro girls managed to move with such ease here,

after living almost exclusively with other Negroes down in Harlem? Someone up

here was as likely to have a brogue accent as a Spanish one. She didn’t mind

the mingling of the races, it was just new: a shock to the system, both in the

streets she walked to go to school and to the market but also in the halls of

Morris High School.

Judy had been eating an apple, her

back pressed against the cafeteria wall when she saw Herbert. He was long faced

with a square jaw and round, black W.E.B. Du Bois glasses.

“That’s all you’re having for

lunch, it’s no wonder you’re so slim,” he said, like he was continuing a

conversation they had been having for a while. Rich coming from him, with his

lanky gait, his knobby knees pressing against his slacks.

A pile of assorted foods rose from his blue tray, tantalizing her. A sandwich thick with meat and cheese and lettuce, potato chips off to the side, a sweating bottle of Coke beside that. For years, they had all lived so lean that it had become a shock to suddenly see some people making up for lost time with their food. Judy finished chewing her apple and gathered her skirt closer to her. “You offering to share your lunch with me?”

Herbert gave her a slight smile.

“Surely you didn’t think all this was for me?”

They were fast friends after that.

It was easy for her to make room for a man who looked at her without pity.

There had always been room in her life for someone like him: one who saw, who

comforted, who provided. Her father, James, grumbled disapproval when Herbert

asked to court, but Herbert came with sunflowers and his father’s moonshine.

“What kind of man do you take me

for?” James asked, eyeing Herbert’s neat, slim tie and sniffing sharply to

inhale the obnoxious musk of too much aftershave.

“A man who wants his daughter to

be loved completely,” Herbert said. “The way that I love her.”

Their courting began. Judy had no

other offers and didn’t want any. That they had James’s blessing before he died

from a heart attack and just as they were getting ready to graduate from high

school only softened the blow of his loss a little. As demure and to herself as

she usually was, burying her father turned Judy more inward than Herbert

expected. In his death, she seemed to retreat into herself the way that she had

been when he approached her that lunch hour. To draw her out, to bring her

back, he proposed marriage.

She balked. “Can I belong to

someone else?” Judy asked Margaret, telling her that Herbert asked for her

hand. “I hardly feel like I belong to myself.”

“This is what women do,” Margaret

said immediately.

The ceremony was small, with a

reception that hummed with nosy neighbors stopping over to bring slim envelopes

of money to gift to the bride and her mother. The older Negro women in the

neighborhood, who wore the same faded floral housedresses as Margaret except

for today, when she put one of her two special dresses—a radiant sky blue that

made her amber eyes look surrounded in gold light—visited her without much to

say, just dollar bills folded in their pockets, slipped into her grateful

hands. They were not exactly her friends; she worked too much to allow herself

leisure. But some of them were widows, too. Like her, they had survived much to

stand proudly on special days like this.

They settled into the plans they

made for their life together. He joined the reserves and, in the meantime,

became a Pullman porter. Judy began work as a seamstress at the local dry

cleaner. Whatever money they didn’t have, they could make up with rent parties

until the babies came.

Now all of that was on hold, her

life suspended by the announcement at the movies that the US was now at war.

The news was hard enough to process, but Herbert’s status in the reserves meant

that this was his time to exit. She braced herself when he stood up to leave

the theater and report for duty, kissing her goodbye with a rushed press of his

mouth to her forehead.

Judy and Margaret had been left to

fend for themselves. There had been some money from Herbert in the first year,

but then his letters—and the money—slowed to a halt. Judy and Margaret received

some relief from the city, but Judy thought it an ironic word to use, since a

few dollars to stretch and apply to food and rent was not anything like a

relief. It meant she was always on edge, doing what needed doing to keep them

from freezing to death or joining the tent cities down along the river.

Her hours at the dry cleaner were

cut, so she and Margaret reluctantly joined what an article in The Crisis

described as the “paper bag brigade” at the Bronx Slave Market. The market was

made up of Negro women, faces heavy for want of sleep. They made their way to

the corners and storefronts before dawn, rain or shine, carrying thick brown

paper bags filled with gloves, assorted used work clothes to change into,

rolled over themselves and softened with age in their hands. A few of them were

lucky enough to have a roll with butter, in the unlikely event of a lunch break.

Judy and Margaret stood for hours

if the boxes or milk crates were occupied, while they waited for cars to

approach. White women drivers looked them over and called out to their demands:

wash my windows and linens and curtains. Clean my kitchen. A dollar for the

day, maybe two, plus carfare.

The lists were always longer than

the day. The rate was always offensively low. Margaret had been on the market

for longer than Judy; she knew how to negotiate. Judy did not want to barter

her time. She resented being an object for sale.

“You can’t start too low, even

when you’re new,” Margaret warned Judy when her daughter joined her at Simpson

Avenue and 170th Street. “Aim higher first. They’ll get you to some low amount

anyhow. But it’s always going to be more than what you’re offered.”

Everything about the Bronx Slave

Market, this congregation of Negro women looking for low-paying cleaning work,

was a futile negotiation. An open-air free-for-all, where white women in

gleaming Buicks and Fords felt just fine offering pennies on the hour for

several hours of hard labor. Sometimes the work was so much, the women ended up

spending the night, only to wake up in the morning and be asked to do more

work—this time for free.

Judy and Margaret could not afford

to work for free. Six days a week, in biting winter cold that made their knees

numb or sweltering heat rising from the pavement baking the arches of their

feet, they wandered to the same spot. After these painful experiences, day

after day all week, Judy and Margaret gathered at the kitchen table on Sundays

after church to count up the change that could cover some of the gas and a

little of the rent. It was due in two days, and they were two dollars short.

Unless they could make a dollar each, they would not make rent.

Rent was sometimes hard to come up

with, even when James was alive, but when he died, their income became even

more unreliable. They didn’t even have money enough for a decent funeral. He

was buried in a pine box in the Hart Island potter’s field. James was the only

love of Margaret’s life, and still, when he was gone, all she said to Judy was,

“There’s still so much to do.”

Judy’s deepest wish for Margaret

was for her to rest and enjoy a few small pleasures. What she overheard between

her parents as a child were snippets and pieces of painful memories. Negroes

lynched over rumors. Girls taken by men to do whatever they wanted. “We don’t

need a lot,” she heard Margaret say once, “just enough to leave this place and

start over.”

Margaret’s family, like James’s,

had only known the South. Some had survived the end of slavery by some miracle,

but the Reconstruction era was a different kind of terror. Margaret was the

eldest of five children, James was the middle child of eight. A younger sibling

left for Harlem first, and sent letters glowing about how free she felt in the

north. So, even once Margaret convinced James they needed to take Judy

someplace like that, it felt to Judy that she always had her family in the

South and the way they had to work to survive on her mind.

Judy fantasized about rest for

herself and for her mother. How nice it would be to plan a day centered around

tea, folding their own napkins, ironing a treasured store-bought dress for a

night out. A day when she could stand up straight, like a flower basking in the

sun, instead of hunched over work.

Other people noticed that they

worked harder and more than they should as women, as human beings. Judy thought

Margaret maybe didn’t realize another way to be was possible. So she tried to

talk about the Bronx Slave Market article in The Crisis with her mother.

Margaret refused to read a word or even hear about it. “No need reading about

my life in no papers,” she said.

Refusing to know how they were

being exploited didn’t keep it from being a problem. But once Judy knew, she

couldn’t keep herself from wanting more. Maybe that was why Margaret didn’t

want to hear it. She didn’t want to want more than what was in front of her.

Herbert’s companionship had fed

her this kind of ambition and hope. His warm laughter, the way she could depend

on him to talk her into hooky once in a while, to crash a rowdy rent party and

dance until the sun came up, even if it got her grounded and lectured,

was—especially when James died—the only escape hatch she could find from the

box her mother was determined to fit her future inside. So, when Herbert

surprised her at a little traveling show in Saint Mary’s Park, down on one knee

with his grandmother’s plain wedding band, she only hesitated inside when she

said yes. It wasn’t the time to try and explain that there was something in her

yawning open, looking for something else, but maybe she could find that

something with Herbert. Her mother told her to stop wasting her time dreaming

and to settle down.

At least marrying her high school

buddy meant she could move on from under Margaret’s constant, disapproving

gaze. They had been saving up for new digs when Herbert was drafted—but now

that was all put on hold.

The dream had been delicious while

it felt like it was coming true. Judy and Herbert were both outsiders, insiders

within their universe of two. Herbert was the only rule follower in a bustling

house full of lawbreaking men and boys; Judy, the only child of a shocked widow

who found her purpose in bone-tiring work. Poverty pressed in on them from

every corner of the Bronx, and neither Judy nor Herbert felt they belonged

there. But they did belong to each other, and that wasn’t nothing.

Excerpted from Women of the Post

by Joshunda Sanders, Copyright © 2023 by Joshunda Sanders. Published by Park

Row Books.

Purchase

Links:

B&N: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/women-of-the-post-joshunda-sanders/1142106285

About the Author:

Joshunda

Sanders is an award-winning author, journalist and speechwriter. A former Obama

Administration political appointee, her fiction, essays and poetry have

appeared in dozens of anthologies. She has been awarded residencies and

fellowships at Hedgebrook, Lambda Literary, The Key West Literary Seminars and

the Martha's Vineyard Institute for Creative Writing. Women of the Post is her first novel.

Keep in touch on social media:

Author website: https://joshundasanders.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JoshundaSanders

Comments

Post a Comment